While this blog originally appeared Oct. 11, 2006, I thought it would be appropriate to post it again and revisit the discussion given the tragedy of recent events at Virginia Tech.

I’m angered that the sort of world we live in is a place where people attack the weak. And I know God is too. But I’m not surprised—or at least, I shouldn’t be. But our secular world is always surprised, and this is most frustrating! Turn on the TV or radio commentators and listen to them discuss in absolute bewilderment how the sort of thing like a school shooting could possibly happen. I say that I’m not surprised by this sort of brutality for several reasons. But the reason that seems most obvious is the one reason that evades our cultural elite.

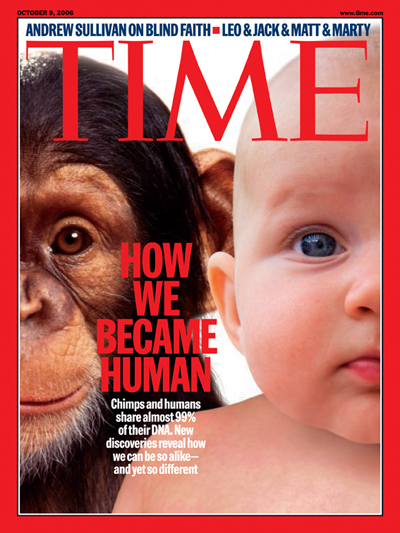

As I was standing in the Safeway checkout line the other night I glanced across the magazine rack to see the current issue of Time Magazine.Â

The front cover shows an infant child’s face, and next to his, what appears to be a young chimpanzee’s face. The text that stands out in the middle of the images reads, “How We Became Human.” The smaller print on the cover goes on to tell the reader that there is a 99% similarity between chimp and human DNA.Â

This post is not meant to be a discussion on Darwinian Evolution vs. Intelligent Design, but merely to point out one of the great inconsistencies in our secular culture. One the one hand, our world ponders why people murder, loot, and exploit—why we act like animals. Yet, on the other hand, our world tells us that we are animals. Whether we’re in biology class or in the checkout line of the grocery store, we’re informed that we are merely the byproducts of time + chance + matter. And here’s the baffling thing. No one can figure out why we treat human life as if it’s no more sacred than the bug on our windshield. If there is no difference between us and the animal kingdom, why not act out what we see in the animal kingdom?Â

You see, if we are the children of King Kong, rather than King God, there is no reason to complain about any human action. It’s also meaningless to use words like “moral” and “immoral.” But if we are the children of King God, there’s good reason to complain when we don’t act like His children. And we all do complain. So the modern secularist lives in a sort of schizophrenia. He or she denounces what is evil, but then argues that there is no such thing as evil. Maybe G.K. Chesterton said it best in his book, Orthodoxy, as he described the mindset and life of a person shaped by today’s secular, schizophrenic culture:

“As a politician, he will cry out that war is a waste of life, and then, as a philosopher, that all life is a waste of time. [He] will denounce a policeman for killing a peasant, and then prove by the highest philosophical principles that the peasant ought to have killed himself….The man of this school goes first to a political meeting, where he complains that savages are treated as if they were beasts; then he takes his hat and umbrella and goes to a scientific meeting, where he proves that they practically are beasts. In short, the modern revolutionist, being an infinite skeptic, is always engaged in undermining his own mines. In his book on politics he attacks men for trampling on morality; in his book on ethics he attacks morality for trampling on men.”

So long as we conclude that humanity is just another sample of accidental biology, the real source of the problem will perpetually evade us. The great Biologist—God—tells us that the problem is that humanity’s “heart is deceitful above all things and beyond cure” (Jeremiah 17:9). The mortal sickness of the human heart is beyond all human cures. There’s no remedy we can concoct to restore health to it, though we’ve believed a remedy might come through education, government, prosperity, and the like. But if the great Biologist, Himself, offers an antidote, there is hope. And this is exactly what God has done.Â

In a passage that is often times misinterpreted to refer primarily to bodily healing, the Hebrew prophet, Isaiah, foretold that God’s Messiah would be “pierced for our transgressions” and “crushed for our iniquities.” He went on to say, “the punishment that brought us peace was upon him, and by his wounds we are healed” (Isaiah 53:5). The healing which Isaiah spoke of was a healing of the human heart. In eternity, that healing will involve the body, as we are given resurrected bodies, but it takes place through an antidote being injected directly into the darkest part of the human person—the heart or soul. From here, and here only, are all things made new. And the only one able to administer the antidote to us is the only one not infected with the disease, namely, Jesus—the God-man. And the startling news is that the antidote and the physician are one and the same. Jesus infuses his divine life into us, through the Holy Spirit. This is true life!

“The person who finds me finds life . . . all those who hate me love death.” — Proverbs 8:35-36

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

1. What things does the secular world blame for the cause of evil?

2. Why do you think the secular world is so resistant to the idea that evil resides in the human heart?

3. Without simply “raising our voices,” how can those of us who are followers of Jesus bring the life-giving message of Jesus to our confused world?

4. What do you think the Psalmists meant when he wrote, “The person who finds me finds life . . . all those who hate me love death” (Proverbs 8:35-36)?

5. Do you agree with the description of the modern skeptic offered by G. K. Chesterton? Why or why not?

23 Comments on “School Shootings . . . Why?”

You say:

It seems that you saying that these two statements are logically inconsistent:

1. Humans and chimpanzees share a common ancestor.

2. Killing school girls is wrong.

So anyone who accepts one must reject the other. Am I interpreting you correctly?

Very nicely said, Brent! I hadn’t thought of that before, but it makes perfect sense. That issue of Time is sitting on my coffee table, and reading that article made me sick. It is scary to think we have a whole generation of young people now who were raised on that stuff and told that it is the only truth out there. I loved the quote from Chesterton; I see that very thing every day on my college campus. The people who protest the Iraq war as ‘immoral’ because it cost the lives of soldiers and citizens are back the next day claiming that a woman should have the right to an abortion if she wants it! It is no wonder that young people are so confused and hopeless: that is exactly what they have been taught to be!

Gavin, I am arguing that if humanity is explainable on merely naturalistic grounds (no intelligent designer), then we are no different (categorically) than any other animal. Further, if Naturalism is true, there exists nothing metaphysical (e.g., good, evil, ideas, truth, God, souls, etc.). Reason being, all of these sorts of things are not physical, but metaphysical—they are beyond the physical. Therefore, within Naturalism, something like torturing an innocent child for the mere pleasure it brings somebody cannot be labeled “immoral� because realties like good and evil are either (1) mere illusions, or (2) human constructions, or (3) matters of individual taste.

I hope this gives a little bit more clarity to what my argument was in this post. If not, please let me know more specifically what your question might be. Thanks, Gavin.

Alyssa, that is a keen observation of how we see this worldview inconsistency even today. I’m likewise reminded of a bumper sticker that I used to see quite often when I lived in Boulder (and still continue to see now here in Ft. Collins) which reads, “Free Tibet!� Now, I’m assuming that the argument behind this statement is something like: (1) it is morally wrong to treat humans cruelly; (2) Tibetan Buddhists are people; (3) therefore it’s wrong to treat Tibetan Buddhists cruelly. However, the problem is that many of the people who proudly display this bumper sticker on their cars do not even believe in such a thing as moral rules that transcend individuals and/or cultures. They would argue that moral rules are “person,� like our favorite flavors of ice cream. So, this worldview inconsistency is a bit like the old example of sawing off the tree limb that you’re standing on.

Brent, Humans could have evolved naturally and then been invited into a special relationship with God. Wouldn’t that make humans categorically different without contradicting common descent? Concepts like “round” and “square” are unphysical, absolute concepts that do not contradict Naturalism. Why can’t good and evil be absolutes within Naturalism?

Gavin, though I don’t necessarily agree, yes, it is at least possible that God could have developed certain hominids until one finally had a large enough brain capacity with which He could have (in someway) joined His image (moral, rational, creative, etc.). But you see that even in this scenario humanity is not being explained on naturalist grounds alone. An intelligent designer is being evoked.

I would agree that moral categories like good and evil are absolutes, and I can explain their existence within the framework of Theism. However, within Naturalism, all one has is matter and energy in one form or another. So, the naturalist must either (1) be able to show which atoms are “evil,� and what “evil� even means or, (2) deny their existence altogether.

Gavin, this point that I am making is not something that consistent naturalists disagree with. A good example of someone who accepts this harsh reality is someone like Richard Dawkins of Oxford University. Dawkins argues that everything about humanity must be reducible to DNA, and that “good� and “evil� don’t fit into a naturalistic universe. For, he understands that a moral law requires/necessitates/demands a moral law giver—a divine mind.

Nevertheless, I think my original point in this post still stands. If we are simply a complex animal, then why shouldn’t we act like an animal?

Brent, I’m not a fan of Richard Dawkins. I see no conflict between being a strict naturalist and a moral absolutist. Wouldn’t compassion be a natural tool for distinguishing good from evil?

Because we know better. It’s one of the benefits of being complex.

This is an interesting topic. I have been thinking about this and really am struggling with walking through it. If we have evolved from apes and what makes something moral or immoral to us? Gavin, from your above answer it sounds like you are saying we are just more evolved beings and our conscious (feelings or ability to relate to others) given to us by God or a creator gives us the grounds call one thing good and another bad. So rewind to the school shooting in Pennsylvania – the guy who committed the crime said that “he had a score to settle.” That he was going to “get revenge for the wrong that was done to him”. Ok so the guy had some built up junk. Let’s just say wrong doing was in fact done to him as a child by elders in the Shaker community (compassion was not shone to him at a young age). Let’s just say he knew killing young children was wrong (he was not mentally ill) – so he knew better. Here where I am confused – he did it anyway…. If he knew that it was wrong, he didn’t care or he felt he had a right to not show compassion and get back at a people that did him wrong. So some how in his mind, he was actually moral and thus acted out his crime. To me that seams a little sick and twisted. Did I follow you right in your explaination? It seams like having compassion or being led by your conscious (or feelings) could lead to some not good actions and behaviors. What would you suggest we use as a differentiator between right and wrong? Please don’t think that I am trying to attack you – I am interested in your view.

Britton, thanks for the challenging question.

Compassion is our moral sense and should be used to distinguish between right and wrong. Metal illness makes this impossible for some, and they need other tools. But even for the mentally fit there are many pitfalls. One is the attractiveness of an “if it fells this right it can’t possibly be wrong” attitude that doesn’t distinguish our moral sense from our other feelings. We have a natural urge to act compassionately, but we also may have a very natural urge to kill our neighbor or hop in bed with his wife. Clearly, not all impulses originate with our moral sense.

While it is obvious that our baser desires do not reflect our moral sense, there are some urges that are widely viewed as being moral but which are also not appropriate for distinguishing right from wrong. One is our sense of justice expressed through a desire for revenge. I cannot pretend to understand what happened in Pennsylvania, but I can imagine a mentally healthy person suppressing his or her sense of compassion to follow a sense of justice, doing something very wrong while thinking that it is right. The urge to settle the score feels like a moral sense, and can be the right tool for certain decisions, but it should never override our moral sense of compassion. I believe that this is why Jesus told so many parables that appealed to our sense of compassion while offending our sense of justice. (For example, the prodigal son, the workers in the vineyard [Matthew 20:1-16], “Turn the other cheek,” etc.) Finally, Jesus went voluntarily to his own unjust death in an act of compassion for all of human kind. Jesus knew how to make a point.

Even when we do turn to our compassion to make moral judgments, we can make many mistakes. We can misjudge the feelings or desires of others, we can fail to predict the consequences of our actions, and we can naively assume that others will appreciate our compassion or respond in kind. Applying our moral sense takes tremendous practice and reflection, just like Bible study.

I think that our moral sense evolved naturally. (I wouldn’t use “just,” since this is a rather remarkable event.) I also think our ability to do math evolved naturally, but this does not mean that I think the digits of pi are illusions, products of chance, social constructs, or personal preferences. The digits of pi are what they are and we have evolved the ability to calculate them, difficult though it might be. Right and wrong are what they are, and we have evolved the ability to know them through our moral sense, though it is often far more difficult than calculating pi.

I am anxious for your criticism of these ideas, as my understanding still developing.

Gavin

Brent, back to the original topic, thank you. I join in w/ Alyssa in saying that this subject has never been presented, to me,in this way. It’s so clear and so right on. If the “world” truly understood the supernatural battle going on around them, they’d know the answer to the “why?”. Thanks again.

Gavin, you said: “Wouldn’t compassion be a natural tool for distinguishing good from evil?”

Not always. As an example, say that Man A kills a rich man and takes all his possessions. Assume that he will not kill again, since he now has all the material possessions that he desires. Now assume that you are his judge. Compassion alone might lead you to release the man and allow him to keep the dead man’s possessions – but I doubt that you would find that outcome “good.” Justice is also “good,” and it can’t always be trumped by compassion. There is an absolute right and wrong, independent of our conception of it, and I would argue that the only universal definition of “good” is “that which is consistent with the nature of God.”

We do have “natural tools” for distinguishing good from evil, but those tools point us toward the existence of a moral standard outside of ourselves. The fact that we are born with a sense of morality at all is amazing, considering that without training we “naturally” tend to violate that morality at every turn. This, to me, is an indication that the origin of our morality is not totally biological; what good is a biological impulse that contradicts so many of our other impulses, that is so often unattractive, and that we so easily ignore? I am not arguing that morality can’t be biologically coded, but that the human moral sense is unlikely to have developed on its own. More importantly, what possible meaning of “good” and “evil” can there be in the random assortment of atoms? If the moral sense is just “there,” like the electromagnetic force, there is nothing inherently wrong with trying to avoid it.

All this says nothing one way or the other about the rest of biological evolution, or even the physical origins of humanity. What it does address is the existence of humans as spiritual creatures made for our creator. Whether He created our bodies entirely through evolution, or traditional creation, or something in between, we are more than biological creatures. If the human soul lives on after biological death, it is not a biological construct and could not have evolved. The Scripture that says that we are created in His image seems relevant; whatever our biological history, our spiritual/eternal nature has been changed to allow a relationship with Him.

So, evolution or creationism or whatever, we are fundamentally different from animals due not necessarily to our biology, but to the (non-physical?) parts of us which are “made in His image.”

Wow, I just realized that I’m replying to very old posts… Oh well, here goes anyway. 🙂

I am an atheist. I have a sense of compassion. I can distinguish good from evil. Just like you, I am shocked by these murders.

What do you suggest we do to prevent heinous acts like these?

Gavin, you said: “I am an atheist. I have a sense of compassion. I can distinguish good from evil.” – I’m sure you do…. And just to make sure this is clear, believing in God definitely isn’t required for a sense of morality. I do, however, think that the existence of God (regardless of how we feel about it) is required for an objective good and evil to exist, and for morality to have any real meaning. Have you ever read C.S. Lewis’ “Mere Christianity,” by any chance? It talks a lot about morality. I reached the intellectual part of my faith through a different route, but it’s a great read.

As for your other question… We can’t prevent them altogether, as we live in a flawed world. We can love the people around us, pay attention to their needs, and as believers, we can pray. We can try to keep families intact and our children loved, secure, connected, and grounded. Some people may be called to work with victims’ families or with criminals as counselors, ministers, etc. All these things are things that we need to do anyway, not just to prevent these events.

I also wish that the media didn’t cover sociopathic disasters so obsessively – I think the media coverage might make such acts more attractive to certain people. I also think that extremely violent media and games are a real problem for some kids, and can break down emotional barriers against violence that we are better off keeping intact; so, although I’m not for censorship, I think that we should avoid supporting those things with our money and we should be responsible for limiting our kids’ (and our own) exposure to them.

I have some C.S. Lewis on my shelf, but not “Mere Christianity,” which surprises me because I know I’ve read it. I’ll look around some more.

Is the existence of God required for an objective black and white to exist, or loud and quiet. If I don’t need God for plaid and paisley to have real meaning, why do I need him for good and evil?

I really love the rest of your post and second everything you wrote, even the call to prayer. (I don’t think I am actually communicating with anyone other than myself, but time to reflect and focus is essential.) When we have these debates I think it is important to keep in mind that we generally have the same goals and agree on most actions.

The reason I point this out is that there seems to be a sense that if I don’t go to God for my morality, then I’m not really moral (or my morality is confused or hypocritical). This seems to be one of the main points of Brent’s post. (Am I right Brent? I don’t want to put words in your mouth.) I find this view mistaken and divisive when we could be finding so much common ground.

I don’t think that anyone says that you are not really moral because you don’t consciously go to God for your morality… I am just saying that, whether a person realizes the fundamental source of their morality or not, the contention that there is an objective good and evil that is not merely opinion (i.e., the Nazi ideology was objectively evil, not just evil because we wrote the history books) ultimately logically requires the existence of a God who is both perfectly good and a Personality.

You ask: “Is the existence of God required for an objective black and white to exist, or loud and quiet. If I don’t need God for plaid and paisley to have real meaning, why do I need him for good and evil?” – Basically, the answer is that light and noise and our perceptions of them are explainable by physics. Physics alone cannot explain why good and evil should have any real meaning beyond the bouncing of atoms in our individual brains. Actually, this makes for a pretty good parallel. The “substrates” required for black and white to exist are full-spectrum light (photons with varied wavelengths) and the physiology (eye/brain) required to perceive it. The substrates required for loud and quiet to exist are atmosphere and compression waves and the physiology required to perceive them. The substrates required for good and evil to exist are the completely good God and the physiology required to perceive good and/or act on it. All of the above rely on the comparison between a standard (full-spectrum light, a certain level of noise, or God’s nature) and its absence (black, quiet, evil). One difference is that, while we know that light is real, we don’t believe that black and white have any real meaning beyond our perceptions of them – yet somehow we persist in assigning real meaning to good and evil without any physical rationale for their existence.

Years ago, one of my college professors (an athiest, like many of my professors) during our semester on “Western scientific materialism” talked in class about this paradox – he said that, although he couldn’t assign real meaning to good and evil because his philosophy left no room for actions in the universe beyond the physically observable interactions of matter and energy, he still lived as if good and evil did exist. He was as moral as any of us, but he couldn’t explain why he felt the urge to be moral, or to live as if morality has meaning although he believed that it had none.

Back to your point – I would never say that you are not moral. Rather, I would say that the fact that you ARE moral, or try to be, in spite of the lack of a naturalistic explanation for good and evil, is a signpost to a greater reality that almost all of us are aware of on some level. Our recognition of Good is an indication of the nature of God. The very fact that you desire to be good, or moral, is an attraction to what I would argue that we are made for; an intimate relationship with the perfectly Good. I think that the desire for Good is a huge gift; much better if we follow where it ultimately leads.

Oy, #15 looks long. Sorry!

Heather,

Thanks for the thought provoking response. I’m confused still. God seems to be playing two roles, one as a “substrate” and one as a standard for comparison. I don’t understand the substrate argument. I see white things by perceiving the light that they scatter. I hear loud things by perceiving their sound. My only perception of the VT shootings was also through light (scattered off on my news paper and emitted by my TV) and sound (from my TV and radio) as well. The way the information got to me was explainable by physics. Where is the God substrate?

I think I understand the other concept of God as a standard for comparison. When I hear news of a shooting spree, for example, I have to compare this act to a perfectly good God to decide if it is evil. Am I understanding this correctly?

However, when I perceive something as white, I don’t have to compare it to a standard that is perfectly white. I’ve seen things that are very white, and things that are very black, so I can extrapolate to an imaginary ideal that is perfectly white, even though perfect white doesn’t exist. Since I’ve seen actions that are very good, and some that are very bad, can’t I extrapolate to a notion of perfect good even if nothing perfectly good exists?

Do I even need to imagine a perfect standard? I can say, “I don’t know what perfect evil (or good) would look like, but walking around shooting people is, without a doubt, very evil.” I don’t need a perfect standard, just some means of perception, which I believe is a sense of compassion. I don’t think compassion requires God.

Thanks for reading my inexcusably long post, Gavin. 😉

Gavin, your statements are in quotes.

1. ” I see white things by perceiving the light that they scatter. I hear loud things by perceiving their sound.”

The substrate thing is just a metaphor to draw a parallel with your illustration. You asked if an objective morality couldn’t exist like an objective black and white, and I pointed out that black and white themselves don’t exist on their own – they require there to be certain characteristics of light and a biological means of perception. Morality likewise can’t exist on its own, as some mysterious independent natural law… It requires certain characteristics of reality (which I argue include a moral Personality) and the biological means of reaction to those characteristics. Sorry about the confusing terminology. (Too much biology in my head, I guess. It messes up my analogies. ;))

2. “The way the information got to me was explainable by physics. Where is the God substrate?”

If we believe that there is such a thing as real morality independent of our individual opinions, that “real morality” is not explainable by physics. Therefore, in our own minds, we simultaneously assume on one level that there is a super-physical reality and, on another level, sometimes deny the existence of that super-physical reality. To keep our belief in the real existence of morality, we eventually have to either (A) abandon our belief in morality, (B) consciously admit the existence of a super-physical reality, or most commonly (C) ignore the irresolvable conflict between our beliefs and go think about something else instead. Once that super-physical reality is accepted, I think that a personal moral God follows – but the existence of the super-physical itself is the problem that strict naturalism denies.

3. “I think I understand the other concept of God as a standard for comparison. When I hear news of a shooting spree, for example, I have to compare this act to a perfectly good God to decide if it is evil. Am I understanding this correctly?”

Well, a shooting spree goes so far against our sense of right and wrong that we instinctively know that it is wrong. I’m saying that God is the ultimate standard, whether we’re conscious of it at a given moment or not. You have mentioned compassion; as I mentioned in post #11, compassion alone doesn’t always define right and wrong. More fundamentally and importantly, what makes compassion good? Not physics…

I think the most basic point of my posts is that, as in point #2 above, the existence of an objective right and wrong is unexplainable by physics and therefore, if we presume that they are real, the super-physical must exist. How do you feel about that? (If we don’t agree on that, discussing the nature of that super-physical reality is putting the cart before the horse. 😉 )

Heather,

First, I’m glad you referred to your post #11 above because I missed it. Your #11 probably appeared while I was writing #12 (which was a response to Brent’s decision to again link secularism with brutality, not a response to your post). It is a good discussion. Compassion would certainly not lead me to release the murderer and allow him to keep his victim’s possessions. Compassion requires consideration of the wider effects of such a response, which would almost certainly be similar crimes by people anticipating similar leniency. These crimes would cause great suffering, so punishment that discourages future crimes would be compassionate if it is not excessive. So I’m not convinced that there are situations where compassion does not define right and wrong.

Thanks also for narrowing the focus at the end of your last post. This is indeed the place where I think we disagree. If you don’t mind I would like to shift the counter example from black and white (which are easily explainable using basic physics) to the slightly more challenging notions of liquid and solid.

Certainly we can distinguish between objects that are liquid and those that are solid, and we believe that distinction reflects something real about the world. None the less, we cannot explain the concepts of liquid and solid in terms of basic physics. Starting from a theory of electrons, protons, neutrons, and their fundamental interaction, we do not know how to predict the existence of liquid water or solid ice. The interactions are all well understood, but the specifics of atomic orbitals and intermolecular forces quickly get so complicated that we are hopelessly confused. There is a real sense in which liquid and solid are not explainable using physics, even though they are real properties of substances and we have the biological means to perceive them.

Now, there is good reason to believe that liquid and solid are explainable in terms of physics, even though no one can do it. I think there is good reason to believe the same about right and wrong. Certain actions cause suffering and sadness, other actions promote joy and satisfaction (not just in the moment, but in a larger sense). I cannot explain those feelings in terms of physics, but since our brains seem quite clearly to be governed by the same physics as other matter, I expect that such an explanation exists. We certainly are able to perceive our own suffering and joy, as well as the feelings of others. When we are compassionate, we consider everyone’s feelings, including our own. Those things that cause suffering are wrong while the actions that lead to the greatest happiness are right.

So, I think right and wrong can be defined in terms of people’s emotions (which we have the ability to perceive) which are based on their biology, which is based on chemistry, which is based on physics. I don’t think anything super-physical is required.

Gavin,

“Compassion would certainly not lead me to release the murderer and allow him to keep his victim’s possessions. Compassion requires consideration of the wider effects of such a response, which would almost certainly be similar crimes by people anticipating similar leniency. These crimes would cause great suffering… So I’m not convinced that there are situations where compassion does not define right and wrong.”

What if, hypothetically, you could be sure that releasing the murderer would not encourage similar crimes – somehow, no one would know. Would releasing him with his gains then be the right thing to do? It would be the most compassionate action, but I still believe that it would be wrong.

Although I don’t think that the compassion/suffering criteria are quite universal, even if they are, there is a more basic question. What makes “things that cause suffering ” evil and “actions that lead to the greatest happiness” good? That basic preference biologically is a preference, but that doesn’t mean that the preference is right or wrong. If right and wrong are more immutable than the “wetware” in a human head, they must be super-physical.

Heather,

Why is releasing the murderer with his gains the most compassionate action? (I think you are knocking down a straw man.)

The digits of pi are more immutable than the “wetware” in a human head. Are they super-physical?

Gavin,

The murderer example is just an example of the tension between justice and mercy that morality often has to deal with… There are many virtues, and it’s not always easy to decide their proper balance in a given situation. Our culture tends to consider mercy/compassion the “trump card;” cultures at various times in history have valued other virtues (physical courage, chastity, honesty, etc.) above mercy. Any of the virtues can be used to justify the wrong action in some cases, particularly when our emphasis renders all the other virtues unimportant by comparison. We can keep talking about the hypothetical example if you like, but my point is that there are cases in which a compassionate action can be wrong – for example, when it is unjust, cowardly, dishonest, etc. However, even if mercy DOES trump everything else – WHY? What is the reason behind that standard?

The reality behind the idea of pi is a physical constant in the universe. (The digits themselves are cultural.) The electromagnetic force, strong force, weak force, and gravitational force are physical laws in our universe. They presumably exist independent of our observation, participation, and even our existence. I don’t believe that any physicist has ever postulated morality as a physical law in the universe.

Heather,

I decided to reread all of the posts in this thread because I think I’ve lost my focus in the seven months since my first comment. I’d like to move this discussion to some sort of resolution. I’m currently participating in some other threads and I don’t want to become a pest dominating Brent’s blog.

The point I was initially trying to make was that it is possible to have a right and wrong within naturalism. I suggested compassion as a reasonable way to do this, but I want to get away from the discussion about whether compassion is the correct way in every situation. I’m not an ethicist, and my goal is not to completely solve the problem of discerning good and evil within naturalism.

Brent’s claim was not that naturalism prevents proper discernment in some situations, but that naturalism precludes discussion of good and evil altogether. He used the example of torturing children as something that could not be classified as evil within naturalism. This position I found both absurd and offensive.

Naturalism can deal with abstract absolutes, Pi being an example. We do not need a prophet or prayer to tell us the value, anyone can calculate it (though it is difficult and few know how). Still, the value of Pi isn’t just a property of our brains, a social construct, or a matter of individual taste, it has a specific immutable value determined by some basic principles.

Right and wrong could be the same way. There may be some basic principles, like compassion, that would allow us to distinguish right from wrong (in some cases, at least) in a universe without God. In the case of torturing children, a naturally evolved sense of compassion seems up to the task.