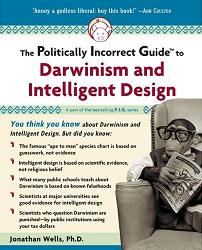

Have you ever heard of the popular series of “PIG” books? “PIG,†or Politically Incorrect Guides is a series of books which Regnery Publishing is putting out. One book of particular interest in the PIG series is Jonathan Wells’, The Politically Incorrect Guide to Darwinism and Intelligent Design. Wells’ book has been a top seller since its release in August of 2006 probably due to it clear and non-technical explanation of the issues surrounding the conflict between Darwinism and Intelligent Design.

The most recent edition of the “Christian Research Journal” (Vol. 30, No. 4) features an article by Concordia Univ. philosophy professor, Angus Menuge entitled, “Is Methodological Naturalism Essential to Science?â€Â So, here’s Menuge’s brief review of Wells’ latest “PIG†book. I’d be interested to know if any of you have picked up Wells’ book and what you think of it.

“The international news media woefully have misrepresented the debate between Darwinism and intelligent design. Sometimes this is due to bias, but more often it reflects simplistic perceptions of the philosophically and scientifically sophisticated issues involved. Happily, Jonathan Wells, postdoctoral microbiologist and leading proponent of intelligent design (ID) theory, is a gifted expositor.

Manipulation of Definitions. Critics of ID frequently focus on several uncontroversial definitions of evolution—’change,’ ‘genetic recombination,’ ‘descent with modification,’ and suggest that because they are uncontroversial, any criticism of evolution is absurd. As Wells points out in the first chapter, however, the real issue is whether the proposed Darwinian mechanism of change (mutation and selection) is adequate to explain the structure and diversity of all life.

Many critics also seek to define ‘science’ in such as way that design cannot be a scientific category. It is now common to claim that methodological naturalism—the view that scientists should only consider natural causes (undirected chance or necessity)—is essential to science. Wells notes, however, that methodological naturalism may actually conflict with the scientific method: ‘If a person refused to question the doctrine of universal common ancestry simply because it is the best naturalistic explanation available, even though fossils cannot provide evidence for it and the molecular evidence is inconsistent with it. . .then that person is no longer engaging in. . .science: namely, determining which hypotheses best fit the evidence.’ (p. 134).

Underwhelming Evidence. Wells’s book is not primarily a work of philosophy. Most of the chapters aim to show the weakness of the evidence for Darwinism, and to explain the contemporary case for design.

Darwin argues that life developed gradually in a tree structure, starting with some primitive, universal common ancestor in a ‘warm little pond,’ and then branching out into the diverse kinds we see today. He admitted that the ‘Cambrian explosion,’ the geologically sudden appearance of the main divisions of the animal kingdom, was a serious problem, but suggested that the necessary transitional forms were too small or soft to fossilize. As Wells documents in Chapter 2, however, scientists have since discovered that small, soft-bodied Cambrian animals do fossilize, so the lack of transitional forms remains a problem.

Chapter 3 focuses on Wells’s area of expertise, embryology. Darwin thought that the similarity of embryos across species in early stages of development argues for a common ancestor. His claim, however, largely rested on Ernst Haeckel’s drawings of embryos, which have since been shown to be fraudulent. Some have rationalized the reprinting of these diagrams in biology textbooks, claiming that they point to the basic ‘truth’ that embryos are similar in their earlier stages. Not only is this an exercise in shabby utilitarian ethics, it is factually wrong. Wells points out that the claim is not true: ‘In the gastrulation stage, a fish is very different from an amphibian, and both are very different from reptiles, birds, and mammals’ (30).

Wells also shows that molecular studies have not produced a consistent evolutionary tree (Chapter 4), and that strict speciation has never been observed (Chapter 5). The ideal test case is bacteria, because of their short generation time. Bacteriologist Alan Linton concluded, however, that ‘throughout 150 years of the science of bacteriology, there is no evidence that one species of bacteria has changed into another.’ In light of this, it is amazing that Darwinists insist on claiming that their view is as firmly established as gravity (Chapter 6).

Obstacles To Overcome. Whereas Darwinists claim their theory is the only way to understand biology, Wells cites many lading scientists who deny this (Chapter 7). Much of modern biology requires scientists to think of living systems as highly complex machines, and to apply principles derived from engineering and computer science that fit more accurately with a design paradigm.

In subsequent chapters, Wells lays out the case for design, canvassing the contributions of William Dembski (theoretical underpinnings), Stephen Meyer (origin of life), Michael Behe (irreducible complexity), and Guillermo Gonzalez (fine-tuning). Wells ends by a consideration of the educational, political, religious, and legal obstacles that need to be overcome if design is ever to have a fair hearing. The saddest part of the book documents the intimidation of highly credentialed critics of Darwinism.

Wells’s book is an ideal gift for anyone who is convinced intelligent design is without merit, but who is unable to read the technical literature first-hand. The book is accessible yet well-documented, up-to-date, and funny.’”

Read Doug Groothuis’ review of Jonathan Wells’ book in the Denver Journal.